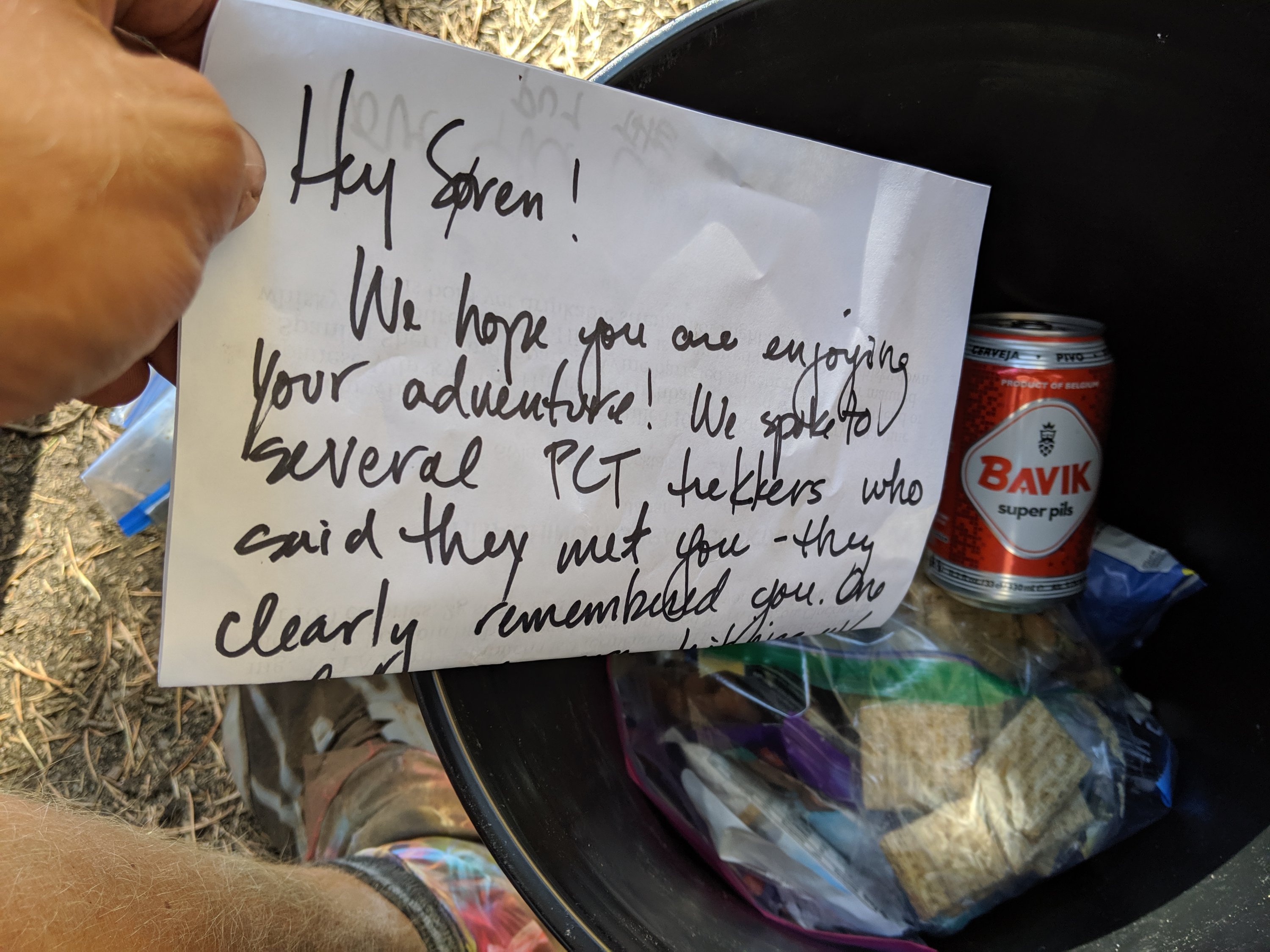

Welcome to my blog. My name is Søren, and I’m hiking the Pacific Crest Trail in the summer of 2019. Read all about it here!

American Pie

I posted this on YouTube and on my social media pages about a week ago, but realized that I may have followers here who won’t have seen it elsewhere. Anyway, this is the project I’ve been working on since the beginning of the hike, and really excited that it all came together well. Enjoy!

Days 139-148: Washington pt III and done

Day 139: Stevens Pass (2465) to Lake Janus (2474)

Day 140: 2474 to White Pass (2503)

Day 141: 2503 to Milk Creek (2526)

Day 142: 2526 to Miners Creek (2550)

Day 143: 2550 to Stehekin (2572)

Day 144: 2572 to Six Mile Camp (2584)

Day 145: 2584 to Rainy Pass/Mazama (2592)

Day 146: 2592 to Harts Pass (2622)

Day 147: 2622 to Castle Pass (2649)

Final Day: 2649 to Northern Terminus (2653) and Manning Park Lodge (2661)

Highlights: Finishing!; Beautiful glaciated and glacially-carved landscapes; Fall colors and berries; Longer nights = great sleep; True sense of solitude and separation from society; Snow makes everything more beautiful.

Lowlights: Fog, rain, and snow; Feeling time pressure to finish due to approaching winter; Noticeably shorter daylight hours.

Stevens Pass to Stehekin

After spending a couple hours in the Stevens Pass lodge finishing my previous blog post, I got to the trail around 3:30 pm on Day 139. As is typical, the weather was cold and rainy, but I was powered on by the motivation of being in the final third of Washington.

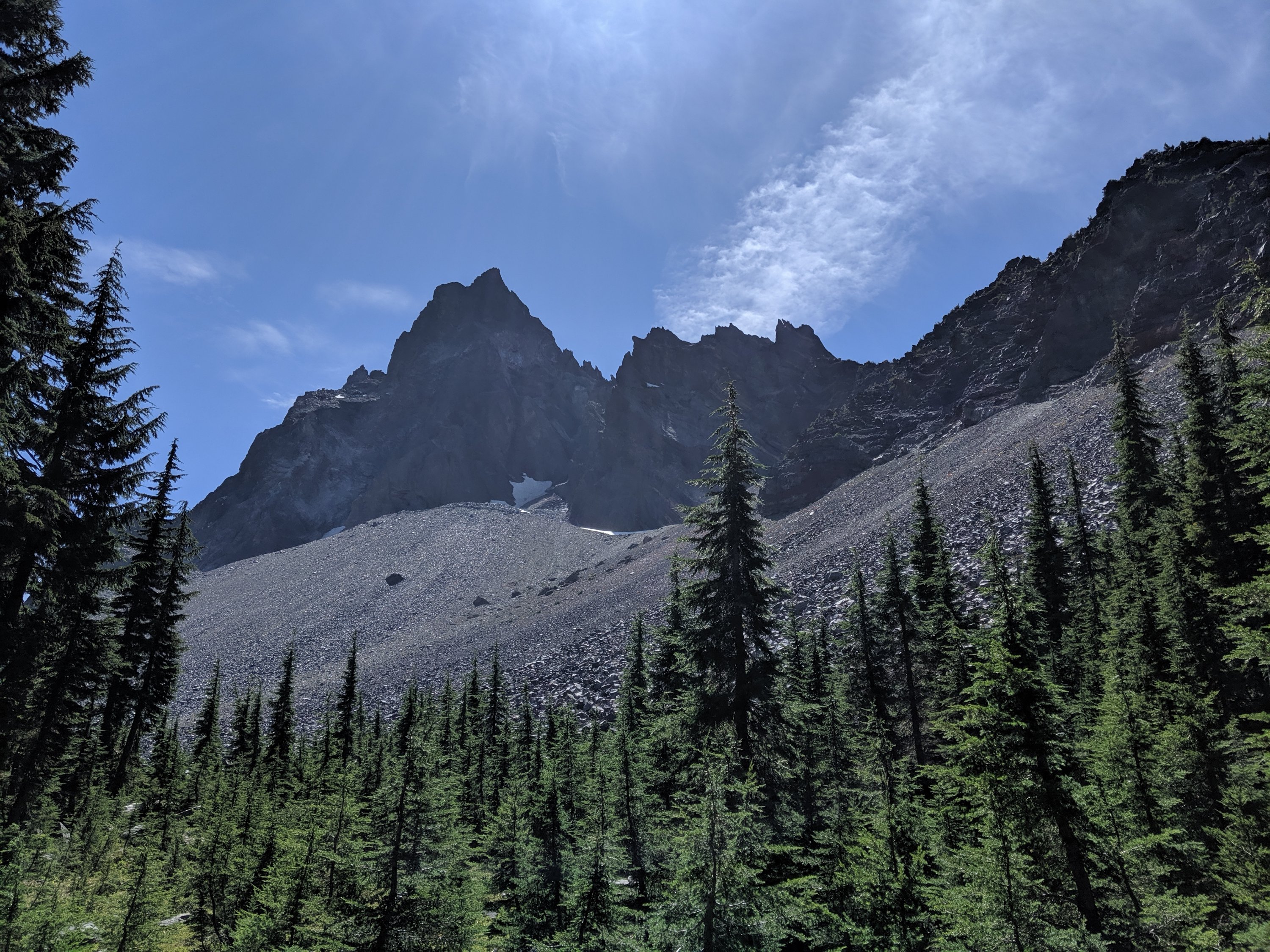

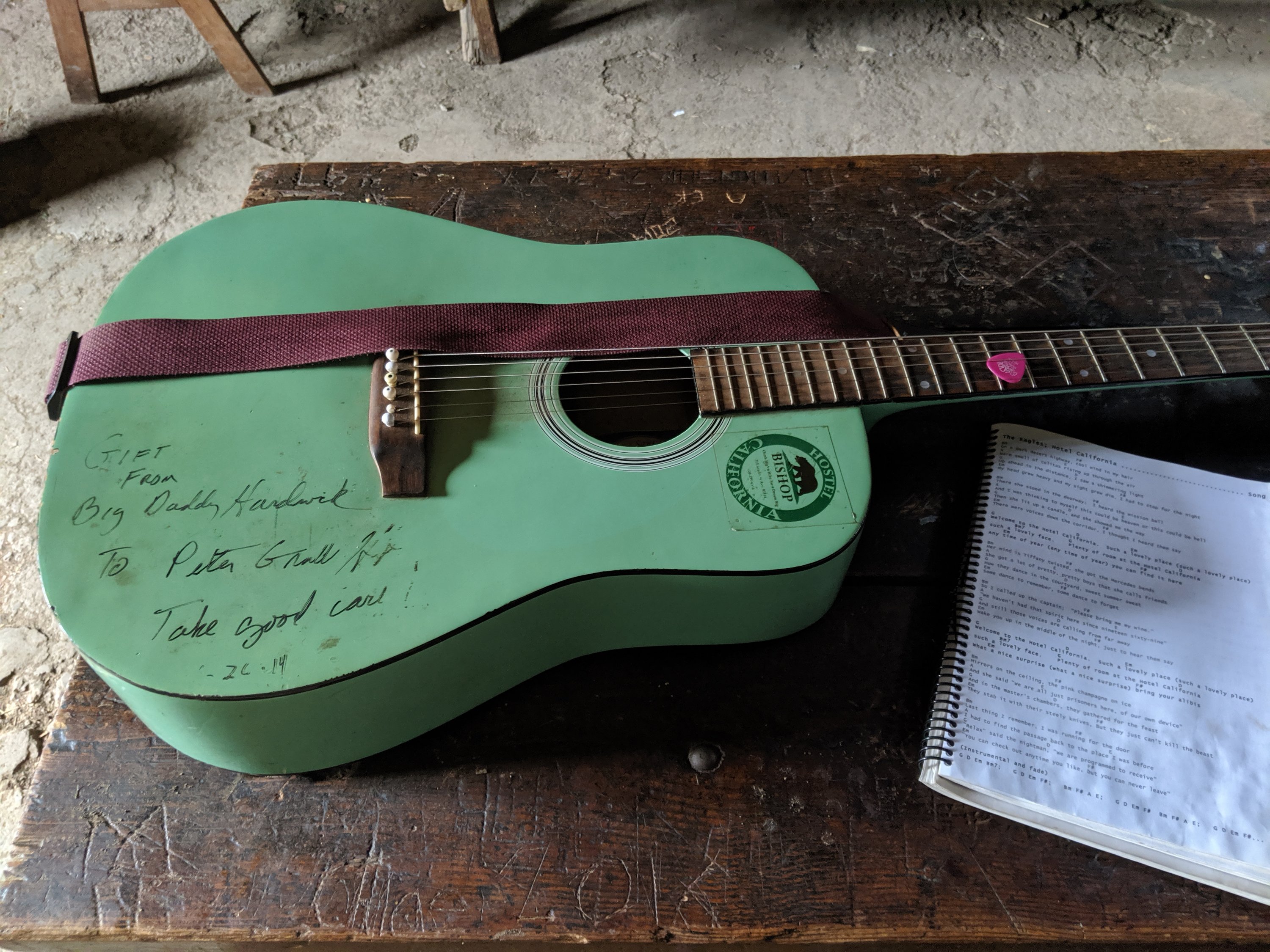

The trail between Stevens and Stehekin is some of the gnarliest trail north of the High Sierra, which made it challenging to do 25-mile days (in contrast to the comfortable 30-mile days I was doing in Oregon). While the southern and central Cascades are generally defined by large volcanos surrounded by mild non-volcanic lowlands, the non-volcanic portions of the North Cascades are jagged ridges with 3-4k ft glacially-carved U-shaped valleys in between. Consequently, the trail in this section includes several massive descents into and ascents out of these valleys, which is a challenge on the legs. Making matters more difficult, about two days of this stretch included lots of blown-down trees, each of which could be time-consuming and/or hazardous to pass over, under, or around. The presence of my guitar protruding a few inches above my head made this more difficult.

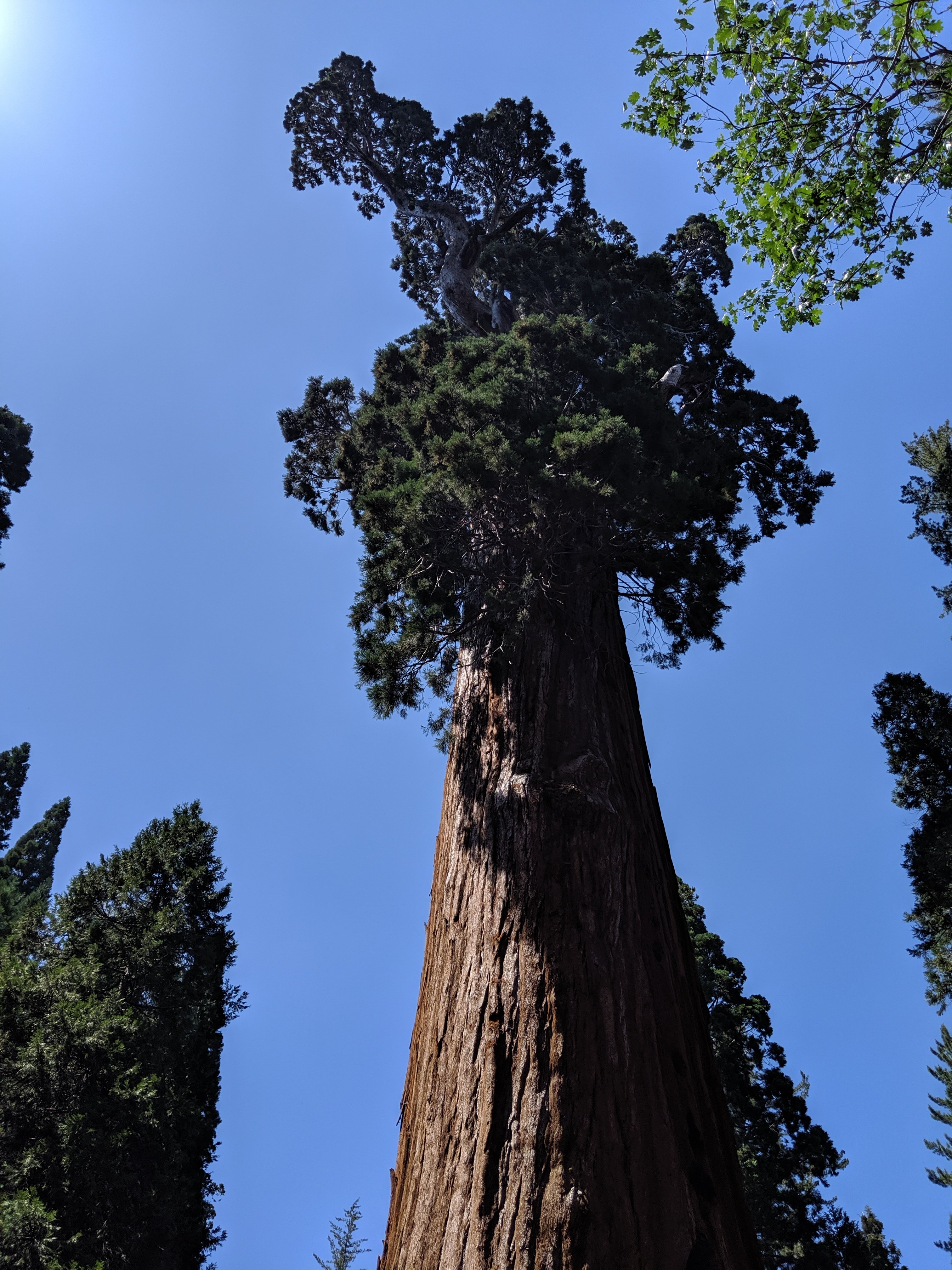

On the plus side, when the weather cooperated, the scenery was splendid. The valleys are your prototypical Pacific Northwest vibe: lots of lush old growth forests, ferns, lichens, damp bridges, waterfalls, etc.

To the contrary, the ridges were generally above the trees, allowing me to see the unpopulated valleys extend for many miles in the distance, and feel a true sense of isolation from society I hadn’t felt since the High Sierra. And for the only time on the trail (probably in my whole life??), I went an entire day without seeing another human being, adding to the sense that I had this place all to myself. I feel like most people will never experience a day without seeing another person, so I feel pretty fortunate to have had that solitude without trying to solo-paddleboard the Atlantic or something.

It is firmly autumnal here in Washington. Above the forest line, the hills are red-orange with the leaves of bushes I cannot identify, and deep red with the leaves of some type of delicious wild blueberry or huckleberry (which slow the pace somewhat). While it is beautiful, the changing colors, daylight, and weather (got a bit of snow on Day 143) is a constant reminder of the approaching winter and the fact that I’m still walking closer to a country known for its winter sports prowess. At the time of writing this paragraph (in Stehekin), it looks like the weather is going to cooperate long enough for me to make it through, but it’s still constantly on my mind.

Stehekin

I arrived to the village of Stehekin in the evening of Day 143, ate dinner in the restaurant, and celebrated the 62nd birthday of a woman in a group I met on the shuttle bus between the trail and town.

I had to pick up a food package at the post office, but arrived to late on Friday, and the post office doesn’t open until noon on Saturday. This meant that I had an enforced morning break in Stehekin, and what a blessing that was, as this is one of the most unique places I’ve stopped on the trail (I’m sorry, I feel like I’ve said that a lot before, but I can’t help it that I keep passing through such incredible places).

With approximately 85 residents (and many more visitors), Stehekin sits on the western edge of Lake Chelan, a very long (55 miles) but quite narrow (no more than 1.5 miles) lake that fills a glacial valley. The high mountains surrounding the turquoise lake evokes Norwegian fjordlands, but what really makes Stehekin special is that it’s totally disconnected from the outside road network. The only ways in are by ferry from the east side of the lake (the most common way, taking 3-4 hours), by propeller plane (now landing on an airstrip rather than the lake itself), or by foot (as I arrived). There are roads and vehicles in the Stehekin Valley (including the shuttle bus to town), but these are all shipped in by barge and mostly never leave (given the duration of the ferry journey, I imagine the barge journey must take an entire day).

This isolation from the rest of the world, along with the dramatic landscape, gives the region a sureal sense of timelessness, that the happenings of the rest of the world simply are not relevant here. A commenter on the PCT trail app described the post office as being out of a Wes Anderson movie, and it is (in the upstairs window, three older women are currently knitting scarves, and the man behind the counter sports long grey hair and beard, and an eye patch), but I think that description applies to the whole town. Much like, say, the Grand Budapest Hotel, things are just a little bit off in all the best ways.

Unlike the average PCT hiker (let alone non-hikers), I had actually heard of Stehekin before arriving here: my park ranger friend Marissa used to work in North Cascades National Park and lived in Stehekin (or at least that was the closest town). Several people I spoke to who work in town or in the park service remember her from a few years ago, so that was cool.

The visitors’ center in town featured art created by several locals and itinerant residents, providing a different perspective on how other people have perceived this spot.

Anyway, the list is getting long, but this is definitely a place I want to return to at some point, hopefully with better weather, and maybe stage some ascents of the nearby peaks.

Stehekin to The End

After a stop at the renowned bakery on my way out of town, I made it back to the trail by 3pm on Day 144, and pushed 11 miles to a campsite by nightfall.

Apparently, Days 143-145 were a big snowstorm, but the trail near Stehekin is pretty much all below 4,000 feet or so, so I didn’t notice much until I ascended up and out of the Stehekin River drainage on Day 145. As I approached Rainy Pass, snow began to accumulate on the trail (lower down, there was snow on plants, but it didn’t stick on the ground).

At this point, I think it would be useful to quickly summarize the geography between Rainy Pass and the Canadian border. Rainy Pass is 61 trail miles south of Canada, and is the northernmost highway crossing of the trail (and, not coincidentally, the northernmost road crossing of the Cascades in the United States). Rainy Pass is at about 4,500 feet. 30 trail miles to the north lies Harts Pass, at about 6,000 feet. Harts Pass has a campground accessed from the east by a dirt road. This is the northernmost road access to the PCT in the United States, but it’s kind of out of the way and not on a through route, so rides are harder to come by if they aren’t pre-arranged. The nearest road in Canada is 8 miles north of the border, so the effective distance from Harts Pass to the end is 39 miles (if entry into Canada is arranged) or 62 miles (if the hiker reaches the border but then has to turn back to Harts Pass). North of Rainy Pass, the trail is almost exclusively above 5,000 feet, peaking at 7,100 feet (just a couple dozen feet lower than the Washington high point in Goat Rocks). The mountains are quite rugged here as well, which is of course beautiful, but they command quite a bit of respect/fear as a result.

At Rainy Pass, winter storm warnings were posted warning of the risks posed over the weekend. I was alone, and I knew the trail continued ascending after the pass, so I decided to bail out on the road rather than push on into an intensifying snowstorm.

Within minutes, I got a ride in the covered bed of a pickup truck. The three folks in the cab had been up cross-country skiing nearby (not a great omen for hiking conditions) and decided to swing by the PCT crossing to see if any hikers were doing exactly what I was doing. Turns out one of them is the proprietor of a “hiker hut” in the town of Mazama, 20 miles to the east, where a dozen or so other hikers had bailed to from Rainy and Harts Passes. Four people who arrived after me had actually hiked north from Rainy Pass for 5-6 miles before turning back due to untracked knee-deep snow, so I immediately knew I’d made the right decision and was grateful to have not wasted so much effort in making it. I chilled in Mazama for the rest of the day, eating at the local bourgeois grocery store, chatting to other hikers, and watching movies.

The weather broke the next morning, and all the hikers scrambled to get out to make the most of the weather window, expected to be 3-4 days. The majority were headed to Harts Pass, just 31 miles shy of the border (not including additional miles required to reach a road). One woman had bailed from Rainy Pass but decided to get back on at Harts Pass (thereby skipping the 30 miles in between), because she was nervous about being able to make it all the way from Rainy Pass to the end before more snow came. Of course, I had bailed from Rainy Pass also, and hadn’t skipped any section of trail yet (and didn’t plan to), so her plans made me slightly second-guess my own, especially given the roughly 3:1 ratio of hikers going to Harts relative to Rainy.

Ultimately, and actually with hardly any doubt in my mind, I decided to go back to Rainy Pass and attempt to complete the whole trail without skipping anything. I knew the distance to the end was very achievable in three days in normal conditions, but the reports of deep snow did put a lot of doubt in my mind as to how many miles I could do in a day. On the other hand, I felt quite confident that I could at least make it to Harts Pass safely in that time, and could bail again from there if I had to (possibly until another year if winter had begun in earnest). For me, crossing the Canadian border without having walked the full distance would have felt fairly empty, so I decided to just keep on going from where I had bailed and see where I could get to.

The hiking was indeed challenging once I finished ascending – a few people were ahead of me breaking trail, but for the most part, the trail was covered in knee-deep snow with defined boot prints. In spite of the conditions, I had the fire that one gets when Mother Nature threatens to derail a five-month quest right at the end, and I didn’t drop too much below 3 miles per hour. I eventually caught up to a couple other hikers who were planning to push all the way to Harts Pass in a single day (remember, my backup plan was to get to Harts in three days and bail from there if necessary). We hiked fast and took basically no breaks, and so arrived at Harts Pass by 9 or 10 pm. Having been quite nervous just that morning that my opportunity to complete the hike might have already passed, I was very excited to have made it nearly half of the total remaining distance in a single day. The ground was covered in snow and it was quite cold out, so the three of us spread out our mats in the public pit toilet bathroom. Not my proudest moment, but it was better than being alone in a freezing tent.

The next morning (Day 147), the two other hikers decided they were going to push 40 miles to the border and to the lodge/road in Canada. They briefly tried to convince me to join, but I was steadfast in my refusal: this is an adventure of a lifetime, and I didn’t want to conclude it in such a hectic manner (and also cross the border monument in the dark). Instead, I still did quite a big day for the conditions (27 miles), but stopped 3-4 miles shy of the border, so I could take my time with the experience the next (and final) day.

The weather was bright and sunny on Day 147, really lighting up the snow-covered jagged mountainsides. This area is clearly beautiful without snow, but I generally think that a layer of fresh snow adds another layer of beauty and tranquility to most landscapes, so it was awesome to see such beauty (not to mention that it was awesome to see anything at all, since I wasn’t walking through a cloud like I have been for the better part of three weeks).

I woke up pretty early the next morning and hiked the final four miles to the US-Canada border, arriving at around 9, and staying for about an hour. There were maybe 8-9 other hikers present during the hour, most of whom actually needed to hike all the way back to Harts Pass before the next snow storm. I had been worried that I would get to the terminus alone and have no one to celebrate with, but I think the narrow weather window condensed everyone a bit, so actually it all felt pretty populous.

The mood was jubilant and reverent. Lots of shouting, laughter, tears of joy, some weightier tears (not necessarily of sadness, but of the emotional weight of completing such a major undertaking). A couple of guys there had hiked together from the beginning through thick and thin, and the joy they shared together was so pure that I had to get some candid pictures of their emotions together.

I finally finished my American Pie recordings, to be edited together in the next couple of weeks. In the entire last five months, I avoided ever playing the final two measures of the song, even if I was giving an otherwise-complete performance of it, to save the end of the song for end of the hike. To finally put the final two bars on the end was an awesome way to cap the hike, and I think the jubilation will be clear in the video when I finish putting it together.

After an hour at the Terminus, I hiked another three hours to Manning Park Lodge, in British Columbia, had a lunch of a salmon burger, poutine, and a Molson, and got a ride to Vancouver from the friend of a hiker. I am now in Vancouver for another day before flying back to San Francisco tomorrow, and to London in about a week and a half.

And so that’s it for my grand journey! I’m very proud to have completed it, and very relieved that I was able to snake my way through the dodgy weather at the end without skipping any sections of it. I’m still a long way from home and I’ve been off the trail for less long than some of my breaks while I was on the trail, so the reality of this no longer being my life hasn’t really set in yet. This blog is not yet over: I’ll definitely write some post-trail reflections in the coming days and weeks when I’ve processed it. Plus, I have to report my post-hike body measurements.

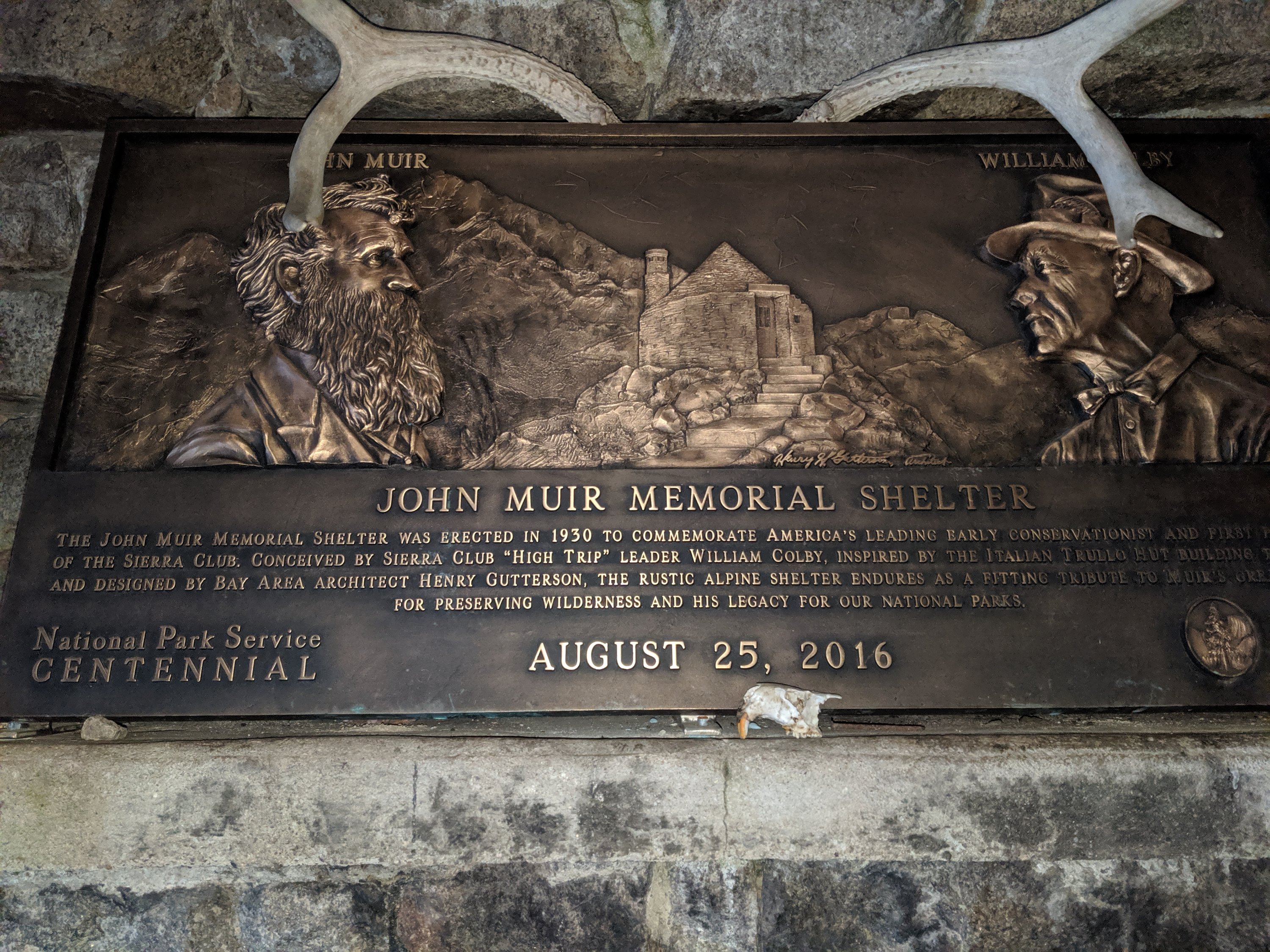

For now though, the main thing that sticks with me is how much time seemed to slow and how eternal it all felt, in a very good way. I think back to standing on the Southern Terminus, or the tranquil beauty of Mt San Jacinto covered in snow, or hiking all night across the LA aqueduct, or sleeping in the hut atop Muir Pass in the High Sierra, or the god-awful treeless volcanic section north of Lassen, or the cobalt beauty of Crater Lake, or hiking 68 miles in 26 hours in Central Oregon, or crossing the Columbia River at the Bridge of the Gods, and it all feels like it took an entire lifetime to achieve. And yet it was all in the last five months. It will never be possible again, even if I were to do a second thru-hike, but I wish I could make every five months feel like a lifetime. Life is short; make it count.

So that’s all I have to say from the trail (or from this couch in Vancouver). Now time to start reintegrating into society, which will probably be harder than anything I’ve done in the last five months.

Happy trails!

Days 131-138: Washington pt II

Day 131: White Pass (2295) to Large Dewey Lake (2321)

Day 132: 2321 to Mike Urich Cabin (2348)

Day 133: 2348 to just north of Stampede Pass (2376)

Day 134: 2376 to Snoqualmie Pass (2393)

Day 135: 2393 to near Delate Creek (2412)

Day 136: 2412 to Waptus Lake (2430)

Day 137: 2430 to Deception Lake (2447)

Day 138: 2447 to Stevens Pass (2465)

Highlights: Friends joining me on the trail; Seeing Chris again; Weather not quite as miserable as I expected; Return to feeling of remoteness.

Lowlights: Cold, rainy weather; Mt Rainier hidden by clouds when the trail passed right next to it; Nightly siege by the mice; Toes rubbed raw by too many days in wet socks.

White Pass to Snoqualmie Pass

Leaving White Pass on Day 131, I had four days to get to Snoqualmie where I had a rendezvous with three friends who are joining for a few days thereafter, as well as a few others coming up from Seattle just for the evening. It’s a 98 mile stretch between the passes, so shouldn’t ordinarily be difficult since 25-mile days are pretty standard for me at the moment. However, rain/showers were forecasted for all of those days, and I didn’t know how much that would affect things.

After a cup of coffee at White Pass, I hit the trail around 9:30. That morning was pretty miserable – cold, rainy, muddy, uphill. At that point, I had about 350 miles remaining on the trail, but even though I knew the weather was temporary, it may as well have been a million miles.

The upside was that I ran into my original hiking partner, Chris AKA Project Runway, hiking southbound around 11:45. We pitched up the fly of my tent to take shelter from the rain, and stopped for lunch. A few weeks ago, he and his group decided that they weren’t going to make it to Canada before the winter hit, so they travelled directly to the northern terminus and started hiking southbound towards Burney, California, the spot from which they had bailed. It looks like they will make it back to Burney, completing their PCT thru-hike, by late October. Although it wasn’t the most relaxing lunch given how cold it was outside, it was still really nice to catch up with him.

The weather was better for the rest of that day and for most of the next day, but I didn’t take too many pictures because there wasn’t much to photograph given the low visibility. This is kind of a shame, because this part of the trail is the closest to Mount Rainier, the tallest mountain in the Cascade Range. I’ve seen Mount Rainier from a distance on this trip and others, but I was really hoping to get an up-close view of it for the first time in my life. Some of my favorite views in recent weeks have been these up-close perspectives on the large volcanoes of the Pacific Northwest, especially Mount Adams and Mount Jefferson, why are you basically have to move your head up and down to see the entire mountain and you can pick out the individual crevasses on the glaciers. As the largest of these, I feel like the view of Rainier would have even exceeded the views of previous mountains, but Mother Nature decided that was not to be. I guess that’s just life in Washington.

On the first night out of White Pass, I awoke in the middle of the night to the sound of a mouse running back and forth inside my tent. In a panic, I opened the door to my tent and hustled the mouse out if there, which was actually not that hard because I don’t think it wanted it to be there any more than I did once it realized there was a human. My tent had been fully zipped up, so I ascertained that the mouse must have chewed a hole into the mesh of my tent and entered that way. Sure enough, I spotted a hole about 1 inch in diameter just to the left of where I sleep. I don’t think that it chewed anything inside my tent, but the hole is annoying, and it’s really disconcerting to feel like the outside world can get into what is supposed to be the shelter from it. It was difficult to fall back asleep, because it turns out that the the pitter-patter sound of rain on the rain fly sounds a lot like the pitter-patter sound of a mouse’s feet, and I was certain that that mouse was going to try to re-enter the establishment. Fortunately it did not.

The next day out of White Pass (Day 132), I spent the night in a hut near a meadow, called the Mike Ulrich cabin. Being the middle of a storm, most hikers within half a day of me seem to have increased or decreased their usual mileage to make it to the shelter by nightfall. It was a nice spot with a wood stove for drying clothes, tents, etc, but a bit crowded. I snagged a spot by the wood stove. I really should have known better, but the mice were rampant that night. While I did hang my food bag on a wall hook, I didn’t really close it up, and the mice chewed at my tortillas, cheese, and a Snickers bar. I had to do some serious trimming the next day to remove the contaminated bits. Even more annoying, they chewed off the pompom end of one of the straps on my fuzzy warm hat. No nutritional value, but I guess the mice don’t care.

Day 133 was supposed to be the worst day of the storm, with my forecast from White Pass a few days earlier calling for 9C / 48F with rain. The rain was pleasantly sporadic for most of the day, only picking up steadily in the evening, so I feel like I dodged a bullet there. That said, another hiker accidentally took one of my socks from the cabin, so I had to go three straight days in one pair of wet socks, rubbing the skin on my toes totally raw by the time I arrived in Snoqualmie and tracked down my other pair of socks.

In Snoqualmie Pass, I was joined for drinks by several friends from Seattle, who came up after their respective work days to a brewery on the pass. I also had three friends I know from London join me for the next four days of hiking: David and Bernat (my current housemate) came in from London; while Lauri came from Austin, TX, where he is currently a PhD student.

I had had friends join me for drinks at a brewery in Cascade Locks outside of Portland, and then here outside of Seattle, so I feel like I’ve made the most of the Pacific Northwest in terms of catching up with friends living in the biggest cities.

Snoqualmie to Stevens Pass

After a pancake breakfast on Snoqualmie Pass, the four of us headed out to the trail by around 11am. In direct contrast to the previous section, the hiking was immediately strenuous, with a c. 3,000 foot climb right out of the pass. The climbs got a bit shorter over the next few days, but still very little was flat – lots of sharp ascents followed by sharp descents.

On the plus side, the weather largely cleared up, so I no longer felt like a drowned rat, and my friends didn’t have to experience the less pleasant side of Washington hiking. In addition, the views were some of the best in Washington so far, with lots of deep glacial valleys, and a sense that we were in locations inaccessible in less than a day’s walk (a first for me since the High Sierra). After a difficult first night being forced to camp on overgrown slopes (due to a dearth of available sites as the sun went down), we had a couple of very lovely campsites next to lakes.

I would ordinarily have hiked this section in three days, but with relatively greener legs in the group, we split it into four days of around 18 miles each. With the shift to more challenging terrain, it would have been a real struggle to do it any quicker. The guys hiked admirably and spirits generally remained high throughout.

As it has been during each of the sections with external company, it was a pleasure to share my lifestyle with the outside world. With Bernat, David, and Lauri specifically, they were three of the five people who joined me for my first real overnight backpacking trip last summer in Northern California, which made it especially special to share the (nearly) end of this journey. The other two people from that trip, my brother Torsten and my buddy Étienne, joined for a few days each in Southern California and Southern Oregon, respectively, so now the whole gang has come along for sections of this hike. Obviously awesome to share my experience with good friends, but equally awesome to catch up with them and be reminded of life back in the outside world: I spend a lot of time in London with Bernat and David, and see Lauri pretty frequently around North America and Europe.

On Day 138, we made it to the end of their hike, at Stevens Pass. We then headed to the town of Leavenworth, about 30-40 minutes’ drive east. For some unknown reason (unknown to me, at least), Leavenworth has decided to theme itself entirely as a Bavarian village, to the point that even Subway looks like it’s wearing Lederhosen, and they have a literal nutcracker museum. A bit of an odd concept, but I really enjoy Bavaria, and it was kind of a kick to see a bit of it placed in the middle of America. Sadly, despite being the third weekend of September, the first weekend of Oktoberfest in Munich, Leavenworth celebrates Oktoberfest only in October. I will be writing a stern letter to the tourism board in due course expressing my deep displeasure.

The next day, my buddies drove me back up to Stevens Pass, where I sit now. It’ll be 8 or 9 days to the end of the trail, during which I expect not to have any cell service, so this will probably be the last you hear from me from the trail.

So with that said, I’ll see you on the other side!

Days 124-130: Washington pt I

Day 124: Cascade Locks (2147) to Table Mountain (2160)

Day 125: 2160 to Panther Creek (2183)

Day 126: 2183 to Blue Lake (2206)

Day 127: 2206 to Trout Lake (2229)

Day 128: 2229 to Killen Creek (2245)

Day 129: 2245 to Goat Rocks – Old Snowy Mountain (2277)

Day 130: 2277 to ???

Highlights: Triumphantly crossing the Columbia River into Washington; Mt Adams; Goat Rocks; Mushrooms the size of dinner plates.

Lowlights: Rainy weather; Weird location psychologically, where I am almost done but the end still feels far away.

Cascade Locks to Trout Lake

I started the morning of Day 124 in a little cabin my aunt Megan had rented in the RV park in town. Joined by my brother Torsten and his girlfriend Sofie, we went for breakfast at a cafe just underneath Bridge of the Gods.

As we were finishing, Jordan, who you’ll remember from various previous exploits throughout my journey, walked through the door. He had just finished the Sierra, flown to Portland, and been deposited at Lolo Pass (just 15-20 miles south from Cascade Locks), and is now finishing his thru-hike in Washington. He had gotten up early and hiked into town, so rewarded himself with an IPA and a Mountain Dew while the rest of us were finishing up our omelets and coffee. He was planning to spend most of the day in town while I wanted to head out, so we split ways again. He’s actually now passed me since I stopped in Trout Lake and he didn’t, so I probably won’t see him again until he backtracks south 30 miles from the border to the nearest road in Washington at the end (the easier thing to do is to continue north 8 miles to the first road in Canada, but he can’t find his passport).

After a quick bit of grocery shopping, which was very limited because Megan and a couple of my friends at the brewery the night before left me with a bunch of stuff, the four of us headed across Bridge of the Gods into Washington. This was my second state line crossing, and definitely much better than California-Oregon, which is just a random spot on the trail marked with a sign. The annoying thing is that the bridge doesn’t have a sidewalk or a shoulder, so cars have to swerve around you. They aren’t going very fast so doesn’t feel unsafe, but it does make it impossible to dilly-dally and properly soak in the moment of crossing the largest Pacific-flowing river in the Americas.

Torsten and Sofie were very much dressed in street clothes, and so only made it across the bridge before turning back. Megan hiked with me for two or three miles before she turned back to go spend a couple of days with other friends in Oregon.

And cue the pouring rain: Welcome to Washington!

I had pretty solid rain for the first two days of Washington, and damp, drizzly weather on the third. This was pretty in its own right, but eventually all of my down stuff (jacket and sleeping bag) got wet, and it was difficult to find the motivation to leave the tent each morning when I could hear the rain drumming incessantly on my rain fly. As a result, my mileage was in the low 20s at first, a big change from the low 30s I was used to in Oregon.

The sun came back out on Day 127, revealing an epic view of the approaching Mt Adams (misidentified in a recent Facebook post as Mt Rainier – sorry about that), and giving me a chance to dry my stuff out in the sun. At the time of writing this, another storm is on the horizon, but these few days’ respite have given me a chance to keep everything dry and think about how I can store things better to keep more of my gear dry.

I made it to a forest service road with access to the town of Trout Lake around 5:30 pm, and got a hitch in the bed of pick-up truck driven by these guys who had been out foraging for mushrooms. Apparently that’s a big thing around here, because there are mushrooms of many varieties and sizes everywhere here. Obviously I know the danger of eating the wrong kind of mushroom, so I have not indulged, but these guys had several pallets and buckets full of apparently the right kinds of mushrooms in their bed, ostensibly bringing them down to some sort of farmer’s market to sell.

I got to Trout Lake and hung out for the evening in the one-stop restaurant/coffee shop/gas station/repair shop thing, with all the staff seemingly able to switch between being a waiter and a mechanic at a moment’s notice. The other building in town is the general store, which was surprisingly well-stocked, including some locally-made cheese which I snagged for the next leg of the journey. I camped that night on the lawn of the general store and, after a lovely breakfast at the cafe and a shower, and celebrating the 75th birthday of Doris (from the general store), I got a ride back out to the trail around noon or 1.

Trout Lake to White Pass

There were several of us in the truck out of Trout Lake, and we all started hiking around the same time. That was nice because then there were people around me for most of that day, which helps pass the time a bit. I camped with a group just on the north side of Mt Adams, which was pretty rad.

Day 129 was my biggest day in Washington, and probably the first day since central Oregon where all the cylinders fired and I just crushed it the whole day. I made it up into the Goat Rocks area, which is so epic it probably deserves a post all on its own.

Goat Rocks is apparently an extinct volcano which has eroded into several smaller jagged peaks and ridges, and is named for the mountain goats which roam the area (I didn’t see any – they may have been out of season). As a result of this process, the scenery is much more jagged and dramatic than the relatively low elevation (<8,000 feet) would suggest. On a day with good weather, as I had finishing the region on Day 130, there are stunning views of the formation itself, as well as out to Mts Adams, Rainier, and St Helens (of 1980 eruption fame). With the addition of large volcanoes in the background and vast evergreen forests down below, it all kind of reminded me of the most dramatic sections of the Scottish Highlands (e.g. the Black Cuillin in Skye), with huge grassy slopes topped with imposing dark cliffs.

On Day 130, I climbed the third largest peak of the formation, Old Snowy Mountain. The PCT doesn’t actually go up it, but an alternate loop goes near the top, and from there it was only a 10 minute scramble to the very top. I certainly lost a lot of time in doing so, but I’m here because I love mountains and epic views, and damn it if I’m going to let a mileage goal keep me from bagging a peak that’s so close to me.

After reaching the top, I scrambled back down to the PCT, which itself followed a pretty impressive knife-edge ridge for a couple miles. This whole area felt much more remote and desolate than anything else since the High Sierra, and makes me excited for what lies ahead in the North Cascades at the northern end of Washington.

The rest of the day took me down to White Pass, a major pass crossed by a US highway and populated by a ski resort. That’s where I sit now, hoping to get a couple more miles in tonight. But by the time this is up and posted, I may just decide to camp here for the night. We shall see!

Days 111-123

Day 111: Shelter Cove (1906) to Rosary Lakes (1912)

Day 112: 1912 to Desane Lake (1942)

Day 113: 1942 to west slope of North Sister (1975)

Day 114: 1975 to Santiam Pass/ Bend (2001)

Days 115-117: Hanging out in Bend/San Francisco/Berkeley

Day 118: 2001 to Rock Pile Lake (2015)

Day 119: 2015 to a meadow (2040)

Day 120: 2041 to Warm Springs River (2065)

Day 121: 2065 to Timberline Lodge (2097)

Day 122: 2097 to a dirt road (2126)

Day 123: 2126 to Cascade Locks (2147)

Highlights: Views opening up to large volcanoes after several days of green tunnel; Visiting family and friends in California; Mile numbers align with years of my lifetime.

Lowlights: Volcanic rock sucks to walk across; Heavy pack out of Bend due to added winter gear; Bad news from the outside world which I basically had to process alone.

Shelter Cove to Bend

After spending most of Day 111 at Shelter Cove on Odell Lake lazing around, writing my previous post, charging things, etc, I finally made it out to the trail by 6 or 7 pm, with enough time to hike up the hill out of the lake and camp in darkness between a couple of other lakes a few miles down the trail.

The first couple of days out of Shelter Cove were mostly quite easy, flat, green tunnel hiking, punctuated by bodies of water ranging from small stagnant ponds to really lovely mid-sized lakes, where we generally stopped for lunch. I continued to hike with Zach and Petr from earlier, and we were additionally joined by Ruthless, a girl from Philadelphia who coded for Google in San Francisco until she decided she didn’t want to be a cliché anymore (she’s also very hesitant to say where she worked, which is why I’ve just put her on blast here).

After lunch on Day 113, the scenery finally opened up into some meadowlands with good views out to the local major volcanoes: Mt Bachelor and the Sisters. North, Middle and South Sisters are all of similar height (probably 11-12k feet) and in very close proximity to each other, and several smaller peaks round out the “family”: Brother, Husband, and Wife.

By the end of the day, we passed Obsidian Falls, known for its large amount of obsidian lying around. I learned from Ranger Dave at Crater Lake that obsidian is chemically identical to pumice, but whereas the latter basically solidified in foam form and is full of air, obsidian solidified under pressure and is therefore extremely dense, heavy, and looks like glass. There was one little stretch that looked like the aftermath of a bar fight, with broken beer bottles strewn all across the ground.

On Day 114 we continued beyond the Sisters. The views were stunning for most of the morning, with clear views north to Three-Fingered Jack and Mt Jefferson (overcast weather meant that Mt Hood was not yet visible). However, the hiking was also possibly the most challenging in Oregon: there was a c. 5 mile stretch of unbroken lava fields, which looked really cool, but the rocks are really sharp and hard, so every step was an adventure.

By 2 or so, we made it to Big Lake Youth Camp, a Christian summer camp which dedicates one of its buildings to hikers in the summer and serves free meals. Thankfully they hadn’t quite closed up lunch, so we managed to eat some chili and potatoes.

One thought occurred to me as I passed mile 1990: if the southern terminus represented the beginning of the Gregorian calendar, and each mile was a year, then I had just spent roughly 20 minutes on every year from the (approximate) birth of Jesus to my own birth. And the next 28 miles would represent my life so far, and some unknown distance in the next couple of days beyond that would represent the entirety of my life. So if the PCT represents the Common Era, then this little sliver of central Oregon represents my life. Deep trail thoughts, dude.

Anyway, I’m a hiker, not a philosophizer. I got to Highway 20 around 6 pm, and pretty easily snagged a couple of hitches into Bend, where I was collected and brought to dinner/drinks by my aunt’s friend Annie, who I knew as a small child but had only reconnected with as an adult in the last couple of years. It was fantastic to visit with her, and also really nice to have a guest bedroom to call my own for a couple of days, and a car to borrow to drive around Bend for my errands. So huge thank you to Annie for your hospitality! I hope the festival has gone well and I hope we’ll get to make music together at some point soon!

In the evening of Day 115, I had a flight from Bend to San Francisco, where I met my mother and brother and some other friends to go to the UC Davis vs Berkeley football game. You didn’t subscribe to this blog to read about the Bay Area, so I’ll spare you the details of my social calendar from the weekend, but here are a couple of pictures.

Bend to Timberline Lodge

I got back to Bend in the afternoon of Day 117 and spent the rest of the day there – by the time I was ready to go, it was too late to start hitching. The next morning, I left for the trail and got to it around 1 pm, as it was a long distance and required two separate rides.

My pack was quite heavy with about 6 days’ worth of food, and my legs were a bit soggy after taking a few days off, so it was a definite slog to try to do a reasonable distance that day. I made it 15 miles, past Three-Fingered Jack but not quite to Mt Jefferson.

The next day, I went around and beyond Jefferson. At this point I should say that Mt Jefferson has been possibly the most unexpectedly awesome view I’ve had. It is not one of the tallest volcanoes in the Cascades, but it’s rather jagged on the top, and highly glacial on the north side. The trail passes goes around the base of it and then ascends the next ridge over, giving some dramatic, up-close, top-to-bottom views of the mountain.

The climb up the ridge was pretty brutal though, and the trail was difficult to find at times. It really took a lot out of me, and I only made it about 25 miles before stopping a bit after 7. I know that sounds alright, but in Oregon it’s hard to justify to yourself doing less than 30 in a full day of hiking.

Around this time, I was receiving piecemeal news about the UC Davis administration shutting down and replacing the Cal Aggie Marching Band, after an investigation found a culture of binge drinking, shady traditions, and harassment. I really don’t want to use blog space to unpack all of this, but my experience in the band was overwhelmingly positive, and I was fortunate enough to be able to lead the band as its Student Director my senior year. For those of you who associate Backstreet Boys’ I Want It That Way with me, that traces back to this halftime show I arranged and directed in the final football game of my tenure in 2012: https://youtu.be/Vg3JKTVV1tY

Anyway, it was probably past due for some disciplinary action and a change of course, but those four years were some of the best of my life, and the organization was/is like a family to me and many others. It really left me feeling deflated, like a whole part of my identity had been erased in a heartbeat. I started feeling better after I was able to talk to some fellow alumni about what it means for the band community, but I had several hours between basically seeing a headline and processing all the implications where I basically only had myself to gripe and mope to.

On Day 121, I crushed it 32 miles into Timberline Lodge, basically only stopping for lunch and at Little Crater Lake, a tiny but deep and super clear pond created by fault action and fed by underground springs. It’s about 50 feet deep, but you can see the bottom very clearly, which is kind of trippy.

The hike into Timberline had some sweet views of Mt Hood, the tallest mountain in Oregon. Timberline Lodge sits midway up the slopes of Hood, and hosts a ski resort and is also a launch point for summiting expeditions. The building itself was constructed as a New Deal public works project in I think 1937, and there’s a cool transcript of the dedication speech from President Roosevelt where he talks about the evolving purposes of our national forests from a resource commodity to a spot for recreation. Interesting spot, and I enjoyed hanging out by the fire and sharing my experiences with the guests of the lodge.

I stealth camped that night in a row of their outdoor amphitheatre, then attended the breakfast buffet in the lodge, which was kind of pricey, but way higher quality that any other buffet I’ve ever been to.

Timberline to Cascade Locks

Headed from there around 10 with the aim of making around 30 miles, so I could take a shorter 20 mile day into Cascade Locks on the Columbia River the next day. With such a late start, I was able to make it 29 miles by around 10:30 pm, but I decided that was probably good enough. Stopped at some pretty neat waterfalls along the way, called Ramona Falls, I believe. There wasn’t a ton of water flowing over them, but it was all very spread out across the falls, like water was dripping from a thousand leaking faucets.

I got up early the next morning to make it into Cascade Locks for the afternoon. I had several friends planning to join at the brewery on the river, and my aunt Megan, who is possibly my most dedicated reader, had traveled from California to hike a few miles into and out of town with me. She hiked to meet me about 4 miles south of Cascade Locks, and we walked into town together. She says she had always kind of thought she would do the PCT one day, and while that ship has now sailed, she is really taking the opportunity of my hike to be able to experience it vicariously, through following not just my blog this year, but blogs and vlogs of several of my fellow hikers. It’s awesome to know other people are vicariously out here with me, but it’s more awesome to be able to share it in person, so I’m very glad she could make it work.

We made it into Cascade Locks a bit before 4 pm and headed straight to the brewery, where we were joined by half a dozen friends of mine from Portland and Corvallis, mostly alumni of the aforementioned marching band. I also have a couple of friends who are touring folk musicians based in Portland. I invited them but didn’t expect them to join because I knew they were on tour, but turns out Cascade Locks was actually directly in between their previous and next tour locations, so they stopped in for a quick beer before they had to head out for their gig that evening. And then also my brother Torsten and his girlfriend Sofie redeemed some Southwest Airlines ticket voucher and came up to Portland and Cascade Locks for the weekend.

So that’s how I ended the Oregon section, surrounded by friends and family in a brewery overlooking the mighty Columbia River, the largest river in the Americas which flows into the Pacific Ocean. I couldn’t ask for a better conclusion to this state, which itself has been unexpectedly awesome with all the epic volcanoes and beautiful lakes. The friend contingent all returned to Portland and Corvallis that evening, but Megan, Torsten, and Sofie all stayed the night and will walk me across the river (and a bit beyond) into Washington shortly.

And now on to my final state!

Days 104-110

Day 104: Ashland (1718) to Porcupine Mountain (1725)

Day 105: 1725 to Vulture Rock trailhead (1756)

Day 106: 1756 to Red Lake trailhead (1787)

Day 107: 1787 to just south of Crater Lake NP (1814)

Day 108: 1814 to Crater Lake Rim Trail (1839)

Day 109/110 (24-hour challenge): 1839 to Shelter Cove Resort (1906)

Highlights: Having company for a few days; Amazing trail magic; Pace has stayed high even with company); Crater Lake; Record hiking distance.

Lowlights: Long water carries; Rain; Occasional difficult volcanic terrain.

Ashland to Crater Lake

After running errands around downtown Ashland all afternoon, Étienne and I headed out to the trail for a few miles in the evening. He was scheduled to take a bus out from Crater Lake on Friday at 3 pm, and wanted to spend a few hours there beforehand, so we had to hike out on Day 104 and then do three 30-mile days to make that.

We got going by around 7:30 the next day. Étienne carried quite a fast pace at first, knowing that 30 miles was quite a stretch and that he would maybe need time for a slower pace in the afternoon.

Early on, we ended up in a predictable but still unexpected water carry. Around 9 or 10 am, Étienne asked where the next water was. I checked to find that it was still 10 miles away, and we each only had about half a liter of water, so we quickly had to switch to rationing mode. From then on I was much more careful to check when the next source was. We had two or three carries of at least 15 miles, so I had to carry substantially more water than I was used to.

Having hiked at quite a pace in the morning, and pushing all the way to the next water source for lunch, we had plenty of time to do the remaining 13-14 miles to reach 31 miles on the day.

The next day was made more challenging by two factors.

First, while the trail in Oregon has mostly been mild and forested (a “green tunnel”), Day 106 went through a lot of lava fields. It’s pretty cool to see remnants of volcanic activity, but it’s also a lot less gentle on the feet and makes it difficult to keep up a good pace.

Second, a rainstorm rolled through starting in the early afternoon. Fortunately, at the spot where we were aiming for lunch, a lovely woman named Clementine had set up a trail magic station. She was staying a week in a town nearby where her husband was for work, and decided to spend her days helping out hikers, having hiked sections of the PCT herself. She had awnings, a grill with hot dogs, tons of snacks, and a charging station. Because it was raining and because Étienne was basically dead from doing 1.5 30-mile days, we stayed for a couple hours, relaxed, treated Étienne’s blisters, etc.

Progress was slower than on the previous day, but Étienne still wanted to make it 31 miles so that we could do a slightly shorter day on the next day and still not fall behind. This meant hiking through the rain until about 10:30, which was a bit unpleasant, but all part of the fun.

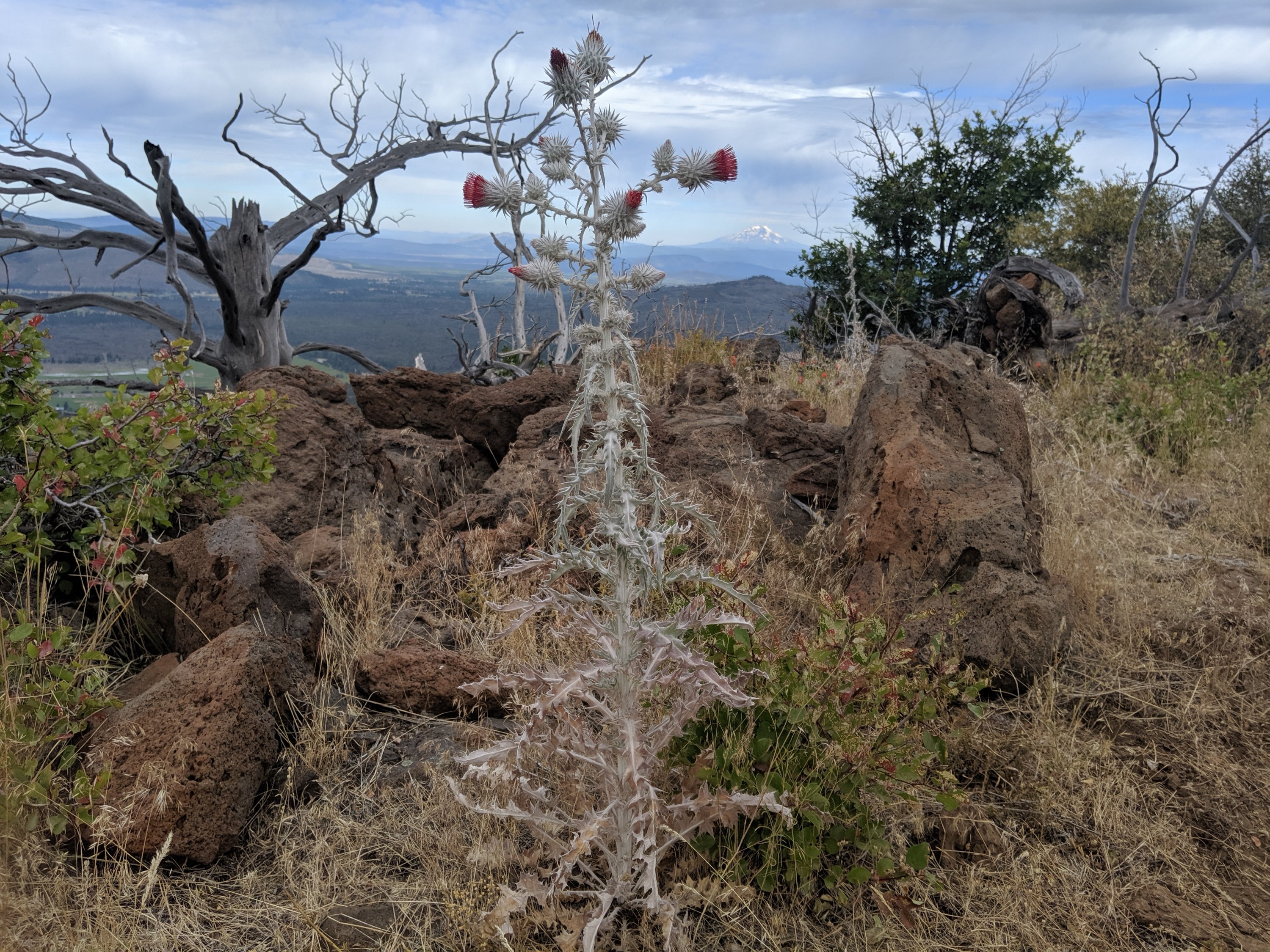

Day 107 took us to just south of Crater Lake. Most of the hiking was back in the green tunnel, but good water sources were still few and far between. We passed through some burn areas near the end of the day which I found quite striking, because they were devoid of life save for some brilliant pink flowers popping up between the charred tree trunks.

We made it far enough on days 105-107 that we only had 12-13 miles into Crater Lake on Day 108, which we were able to do by noon. We ate lunch and checked out the views of the lake, and then went on a two-hour trolley tour around the perimeter of the lake, led by Ranger Dave, whose spiel was full of really interesting facts about Crater Lake and intermixed with terrible puns he’s clearly told hundreds of times (after snapping a piece of brittle pumice with his hands: “Why can’t you trust the Crater Lake rangers? Because they always break their pumices”).

This is my second time to Crater Lake, the first being with a group of fellow members of UC Davis’s Cal Aggie Marching Band on the way to (or from?) a football game at Portland State in 2009. It’s really a stunningly beautiful place, and I was grateful to be able to learn so much more about it that I didn’t get when we passed through in 2009. Here are some things about it:

1. Crater Lake is the deepest lake in the US, just shy of 2,000 feet.

2. It has no inlets or outlets – the water level is maintained by a balance of rain and snow fall on the the lake surface and evaporation. Because it’s basically just pure rainfall without any sediments carried by rivers, it is the world’s clearest lake. The “Secchi disk” used to measure water clarity can be seen at a depth of 130 feet. I didn’t make it to the surface, but this clarity makes the lake brilliantly blue from above (same as Lake Tahoe, which is also deep and clear).

3. About 8,000 years ago, Crater Lake was instead Mt Mazama, a large volcano similar in size to the other noteworthy Cascade volcanoes (maybe 12,000 feet). That’s when a huge eruption happened, and the void left by the departed magma couldn’t support the weight for the mountain, and it collapsed into itself.

4. There were many Native American tribes living in the area. Those to the north were largely killed because the wind was blowing in that direction. The Klamath tribe to the south got lucky and were able to survive the ash fall by chilling beneath the surface of Upper Klamath Lake and breathing through reeds.

5. There are a bunch of creation myths in the oral traditions of villages around which clearly derive from witnessing this eruption. Anthropologists and geologists know they must derive from this, because they all point to an eruption and then a collapse.

6. There are pumice fields all the way up to Bend (100 miles north) which were all created on the day of the eruption, as the aerated lava cooled in mid-air. Pumice is light enough to float on water, and is jarringly light to pick up.

Anyway, here’s a photo dump of the lake:

Crater Lake to Shelter Cove

Étienne caught his bus right after the tour. We had to hike past dark most days, but I was super impressed that he was able to cover 89 miles in 3 days without building up to it. And after some more lonely stretches in the Sierras and getting back into the groove northbound, it was nice to have someone consistent for a few days.

As I walked around the rim and towards my camping spot, it occurred to me that my next resupply spot was about 65 miles to the north, or just over 100 km. A couple of other hikers I know from the beginning of the trip, Petr and Zach, had talked about trying to do 100 km in 24 hours. I decided that evening that conditions were right to try it the next day, and maybe make it to my resupply.

As it happened, Petr and Zach were camped at the same spot as me on the night of Day 108. I told them my plan and invited them to join. They initially declined, as they intended to save their push for the 100 km into the Oregon-Washington line on the Columbia River. Nonetheless, they left camp with me the next morning, and within one or two hours, they decided that it just made more sense to do it with me.

The next 24 hours are a bit of a haze, but ground through the rest of the day and through the night. We generally did 10-12 miles of hiking followed by a 0.5-1 hour break. My legs held up reasonably well, but I was battling drowsiness by the end, especially when we were stopped. We left camp at 8:15 am on Day 108, and got to the 100 km point at 7:28 on Day 109, successfully completing the objective!

By 8:15, we were up to 63.5 mi / 102.1 km, and then it was another 5 miles to Shelter Cove Resort. We kept pushing to the resort, got breakfast, and took a cabin for the night. We were all pretty limpy and drowsy all day, so mostly just napped and watched television.

I’m currently writing this from a lawn at Shelter Cove, where I’ve been for most of Day 111 actually doing the things I need to. I’ll head out from here soon, on my way to Bend!

Days 100-103

Day 100: Etna (1600) to Kelsey Creek (1629)

Day 101: 1629 to Seiad Valley (1656)

Day 102: 1656 to Bearground Springs (1688)

Day 103 1688 to Ashland (1718)

Highlights: Made it to Oregon!; Consistent big miles means I’m making good progress, and my body is adapting; Blackberries.

Lowlights: Quite a lot of sun exposure due to forest fires; shoes literally held together by duct tape.

Wow, a couple of big milestones here: I’ve been at this for over 100 days, and I’ve finally made it out of California! I love my home state, but it’s a gratifying sense of progress to have left it and moved on to Oregon, where the trail becomes smoother and easier.

Etna to Seiad Valley

As I wrote at the end of my previous post, I had hoped to get back on the trail on the same day as getting to Etna. Turns out that wasn’t really possible due to the dearth of vehicles on the road to and from the trail: All my errands were about 2 hours delayed due to waiting that long for a hitch into town, and then by the time I was ready to go back to the trail, around 7 pm, nobody was going back up the hill. So I slept on the lawn of the hostel where I’d already showered and did laundry, and headed out to hitch around 7 the next morning with three other hikers. We managed to get in the bed of a pickup truck not too long after, and were at the trail before 8. Not a bad start for starting in town.

The first day out of Etna was pretty exposed, in part due to fire damage and also partly just because. I passed a couple of really nice looking lakes along the way, but otherwise it was kind of a challenging day out in the sun. Still, I managed 29 miles, which is a pretty solid result for a day starting in town.

Day 101 was much easier – it was only 27 miles into the next town of Seiad Valley, mostly shaded and mostly downhill. In the lower reaches of this descent, blackberry bushes were abundant, both increasing my life satisfaction and decreasing my pace. I’m told that there will be blackberries throughout Oregon, so that’s something to look forward to.

I made it into Seiad Valley by around 6 pm on Day 101, did my grocery shopping at the general store, and set up at the RV park next door.

Seiad Valley is mostly occupied by ranches, with one cafe and general store in the middle, and a bar/grill half a mile down the highway. It is also very much in the heart of the State of Jefferson. Jefferson is a sort of secessionist movement in far northern California and southern Oregon to form a new state (i.e. not secede from the US). California and Oregon politics are both dominated by large, progressive urban areas, and the much more rural Jefferson areas feel that that doesn’t represent them. I used to think of Jefferson as a strictly right-wing Tea Party kind of concept, but now having been through it, it seems more about a rural vs urban identity, and there are actually a decent number of hippies in the area. To use a couple of pop culture references, the woman who gave me a hitch into Ashland described it as “where Shakedown Street meets Deliverance”.

Anyway, Seiad Valley is so Jeffersonian that the sign outside of the general store is just the seal of Jefferson (two offset X’s, apparently representing their disalignment with the rest of California and Oregon), and there are a bunch of signs saying “No Monument”, apparently in opposition to a federal government proposal to designate the area as a national monument, which would presumably hinder the ranching way of life there in some way. I can’t say I agree with that position – environmental policies generally hurt some group of people while benefiting society at large – but I can understand the perspective.

Seiad Valley to Ashland

On the morning of Day 102, I sat down for a breakfast of blackberry pancakes, eggs, bacon, and a blackberry shake in the cafe. The Seiad Valley cafe is apparently famous for its “pancake challenge”, which comprises 5 pounds of pancakes which you get for free if you complete it in two houes. Something like 7 people have ever succeeded. I did not try because I needed to do big miles that day to get to Ashland the next day, and because in order to have any chance of completing it, you basically need to skip the butter and syrup, and that just sounds miserable.

I got to the trail by 8:45 or so. More accurately, I took a bit of a shortcut by walking up a forest service road rather than the actual trail. This avoided me a big, exposed, dry climb, and also cut off 2-3 miles on the day. So while I progressed 32 miles of trail that day, I probably only walked 29. Some hikers view this as cheating, but I don’t – as long as I’m walking the whole way to Canada, I don’t really have any qualms about whether it’s the official PCT or some alternate route.

Apparently that day was also the first day of deer hunting season (bows, not guns), so the myriad dirt roads along the ridge were populated with serious 4-wheel drive trucks. The hunters were all friendly and gave rides up the hill (I didn’t take a ride, because that is cheating according to my personal rules), but it’s definitely redneck culture, while hikers are mostly hippies.

I camped about 4 miles shy of the stateline, and made it into Oregon at around 9 am on Day 103. After hanging out at the stateline for an hour or so, I realized I still had to do 26 miles to get to Ashland that night, so I went into full overdrive, power walking the flats and uphills, and running the downhills. The trail was pretty instantly easier once in Oregon – not too steep, well-shaded, and pretty smooth ground – so this wasn’t actually that hard. I made it to Ashland by 6 pm, which means I averaged 3.25 miles per hour, including a lunch stop. I was pretty fired up about that, and that bodes well for being able to do big miles throughout Oregon without necessarily needing to hike late into the night.

I met two really interesting guys just inside Oregon. They both attempted to thru-hike the trail in 1996, at the age of 23, and got burnt out and bailed after completing California. Now double in age, they’re going to finish the job this year, and were just starting northbound from the stateline. One guy’s trail name is Cyber Ninja or something, because he used to be on the cutting edge of technology back in the day, writing a blog on a PDA and flip phone. This time around however, he’s decided to carry only the same electronics that he had in 1996, so he doesn’t have a phone with him and instead has paper maps, a disposable camera, and a little handheld tape recorder.

Once in Ashland, I met my friend Étienne, who is joining for the next few days to Crater Lake. We got dinner and (too many) drinks, then did our errands the next day.

Ashland is super cute, and easily one of the nicest towns on the trail. It’s home to the Oregon Shakespeare Festival and Southern Oregon University, so it is both a theater town and a college town. It has a very nice downtown, where every single building appears to be an artisinal soap shop or a restaurant. It may be the only town I’ve stopped in where you could just wander downtown without a particular plan and find yourself fully occupied in all the shops. Highly recommend as a town.

Now back to the trail for a few miles tonight (Day 104), so that Étienne doesn’t have to do 30-mile days to make it to Crater Lake by Friday afternoon.

Days 92-99

Day 92: Burney (1411) to near Lake Britton Dam (1421)

Day 93: 1421 to an unnamed ridge (1451)

Day 94: 1451 to West Trough Creek (1482)

Day 95: 1482 to Dunsmuir (1501)

Day 96: 1501 to an unnamed ridge (1526)

Day 97: 1526 to Masterson Meadow (1556)

Day 98: 1556 to edge of Russian Wilderness (1586)

Day 99: 1586 to Etna (1599)

Highlights: Nice views of Shasta and hints of Pacific Northwest vibes (#TeamEdward); Picking up steam with back-to-back 30-mile days; Dunsmuir was a lovely town.

Lowlights: Getting caught in a thunderstorm while camping without a tent; Back-to-back 30-mile days is actually kind of tough.

Burney to Dunsmuir

After a relaxing and pleasant morning and early afternoon eating and shopping in Burney, I hitches back to the trail around 5pm to do a few miles before dark. The trail early on remained low and near a large hydroelectric project, whose dam I crossed after dark that night. I stopped briefly at Burney Falls, a pretty cool waterfall and state park. I would have liked to camp there and see it in the morning sun, and explore the surrounding area a bit more, but I needed to hike more miles that evening.

The following day, the trail quickly left the moonscapy volcanic terrain by Burney and entered into heavy, damp forests, as I imagine Oregon and Washington to be, with occasional open ridge views out to Mt Shasta, the second largest volcano in the Cascade range, after Washington’s Mt Rainier.

In order to keep pace with my goals as well as to prep for more consistent big miles in Oregon, I decided I ought to do two consecutive 30-mile days. I just about managed, hiking slightly after dark both nights, while gaining a lot of confidence in my ability to do so (30 miles increasingly feels standard rather than daunting).

At the end of Day 94, after my second 30-mile day, I camped in a wooded area by a creek with two other hikers. As is my standard practice unless I have a good reason not to, I cowboy camped (i.e. no tent). I’d heard from somebody in Burney Falls that there were supposed to be thunderstorms in two nights (from the point when we spoke), but I thought that meant the night of Day 93, when I did sleep in a tent because I was on a windy ridge and when there was no rain. Anyway, it started raining at about 1 am, and light-up-the-sky lightning began with a frequency of several times per minute not long after. Being down in a canyon and in heavy forests, I was never at risk of being struck, but the mind tends to go in that direction when awoken by heavy lightning.

Additionally, I wasn’t in a tent, which isn’t great for down sleeping bags. My rain fly was nearby, and in my drowsy attempt to rectify the situation, I spread it out over my sleeping bag like a second blanket. At this point, I thought it was like 5 am and that I’d be getting up soon, so I didn’t really feel like expending too much effort. Then I checked my watch to find that it wasn’t even 2 yet, so I very deftly managed to set up my tent poles and put the fly up over them without leaving a seated position inside my sleeping bag. The lightning stopped after probably an hour, but the rain continued for the rest of the night. Most of my stuff got pretty wet, but I was still able to sleep the rest of the night. I guess the same thunderstorm hit all the way up to Washington, so other hikers in more exposed spots had pretty harrowing experiences hoping they wouldn’t get struck. As a side note, why do they call it a thunderstorm? Thunder is only a byproduct of the thing that’s actually dangerous, which is lightning.

The next day, I had a relatively short 19 miles to get into Dunsmuir, a railroad town on Interstate 5 and the upper Sacramento River close to Mt Shasta. The hike down to the road featured occasional great views of Castle Crags, a large cliff formation which looms directly over the road. I remember driving by this in awe a couple of times in high school on my way to go skiing in Shasta with my friend Henry, so Henry, if you’re reading this, this made me think of you.

I got to Dunsmuir at around 5 and was picked up by a hippy woman named KellyFish who runs her house as a hostel. She drove me and another hiker Sugar Rush back there and set us up on the mattresses in the backyard. We then borrowed bikes and rode the remaining 2 miles into Dunsmuir proper for dinner and shopping.

Unfortunately I didn’t take any pictures in town (I really must get better about that), but Dunsmuir was a surprisingly hippy town, given how rural it is. Lots of older homes with fairy lights or artwork hanging on porches or in the window. For the Davisites among you, these reminded me of the homes in Old North Davis (i.e. C and D streets between 5th and 7th). There were lots of restaurants and many people eating in them (this was a Saturday, in fairness). I mentioned this to KellyFish (who also does yoga lessons), and she explained that until a few years ago, Mt Shasta City was the hippy town while Dunsmuir was meth-addled and more typical of the rest of rural California. Since then, many urban refugees from the Bay Area have escaped to Mt Shasta, driving up prices and pushing its hippy population out to Dunsmuir.

Dunsmuir to Etna

I spent the night on a bed outside at KellyFish’s house, cooked pancakes for myself and two others, then hit the trail around 10:30 am. Day 96 was largely uphill, ascending out of the Sacramento River, past Castle Crags, and into the Trinity Alps. I’m meeting my friend Étienne in Ashland, Ore., on Sunday night, and in order to make that, I have to be hiking 30-mile days when I’m starting and ending on trail, and not lose too much time when a town is involved, so I managed 25 miles coming out of Dunsmuir.

During the climb, I came across this couple going southbound (on the much shorter Siskiyou Trail), and the dude (Duncan, I think) noticed my guitar and asked if he could see it. He then proceeded to perform an original of his, which was really well written and performed. Turns out he used to perform in a band, unsurprisingly. Before the trip, I was looking forward to farming out my guitar and hearing other hikers do their stuff. I’ve tried to make that happen, but I’ve been surprised at how few hikers actually play or are willing to perform to an audience. So it was awesome that Duncan was willing and actually really good.

The next three days into Etna were pretty mellow, with primarily ridge walking with good views into lakes and mountains. Classic stuff. I managed 30 miles on the first two of these, and then 13 into Etna on the third. It took like 2 hours to get a hitch into Etna, but had a fantastic meal of poutine and woodfired pizza with some very lovely people I’d met trying to hitch.

Heading back to the trail now – big miles ahead to get out of California and to Ashland in the next few days.

Days 79-91

Day 79: Donner Pass (1153) to Jackson Meadows (1183)

Day 80: 1183 to Salmon Lake Lodge (1210)

Days 81-82: Hanging out at Salmon Lake

Day 83: 1210 to A-Tree Spring (1220)

Day 84: 1220 to Fowler Creek (1245)

Day 85: 1245 to Spanish Peak (1271)

Day 86: 1271 to Chips Creek (1293)

Day 87: 1293 to Little Cub Spring (1316)

Day 88: 1316 to dirt road near Chester (1342)

Day 89: 1342 to edge of Lassen Volcanic National Park (1366)

Day 90: 1366 to Lost Creek (1386)

Day 91: 1386 to Burney (1411)

Highlights: Going north again; Visiting Salmon Lake; Easier hiking conditions than the High Sierra; Hiking with family; Volcanic scenery in Lassen

Lowlights: Leaving Salmon Lake; Lots of forests with limited views; Not as many other northbound hikers as I expected; Long stretch without a proper bed.

I really need to write these more frequently…

Donner Pass to Salmon Lake

After three weeks of really grinding out miles southbound to finish the Sierras, I was now finally back on track to go north to Canada. My mother had picked me up at my exit point in Kings Canyon and drove me up to Davis to sleep and run errands, and then we drove the remaining 1h45 to Donner Pass early the next morning.

I was on the trail overlooking Donner Lake, famed campsite of the fated Donner Party, by 8:45 am. It’s 57 miles along the PCT from Donner Pass to Salmon Lake Lodge, the Christian family business since 1958, and where I’d planned to take my first days off from hiking since I flipped up to Donner Pass in early July.

Last summer, I organized a group of friends and brother to hike from Donner Pass to Salmon Lake, and it took us most of three days. Being in great hiking condition and acclimated to 12,000 feet, I figured I could do it in two days, with the possibility of hiking through the first night and doing it in 24 hours.

I had been up late the night before running errands and doing chores, and up early that morning for the drive, so I figured the 24-hour push wasn’t in the cards this time. Indeed it was not, but I think I could do it were it not for the fatigue and the pain in my feet caused by insoles which are now basically paper-thin (I have just replaced them).

I stopped for lunch on Day 79 at the Peter Grubb Hut, an awesome little cabin in the woods with a small kitchen and common area downstairs and a loft for sleeping upstairs. It’s apparently open year round (I think reservations are required in the winter), so I would definitely recommend it for a short out-and-back weekend trip.

I pushed 30 miles that day, my first 30-mile day on the PCT (I did 30 miles from Paradise Valley to Idyllwild in Southern California, but 3 of those miles were down a side trail which I would then have to climb back up), and camped near Jackson Meadows reservoir, high up the Middle Yuba River.

The next morning I descended into the North Yuba River near Sierra City by lunchtime, and spent the afternoon climbing the long, sunny south face of the Sierra Buttes, a challenging section made easier by the excitement of hiking in the neighborhood of Salmon Lake.

I arrived at Salmon Lake around 6:30 pm, to find my sister Katya partway up the trail greeting me with a beer. My mother and brother Torsten arrived late that night, and I spent the next two days hanging out with them and other members of my extended family (aunts Bev and Sidonie; cousins Owen, Maddie, and Maren), as well as several longtime friends of the family.

Normally when I visit Salmon Lake, I do quite a bit of hiking. Obviously that itch is being thoroughly scratched in the remainder of my life, so this time I pretty much only left the Lodge to drive boats across the lake for guests.

As I was planning my arrival, I remembered that I actually quite like to cook, and have been starved of the experience for quite some time now, so I gave my mother an extensive shopping list so I could get elaborate in the technically-commercial kitchen in the lodge. The first night I made carnitas tacos, complete with pulled pork cooked in a slow cooker and margaritas; the second night I made puy lentil gallettes, a recipe from Yotam Ottolenghi’s vegetarian cookbook Plenty. After three months of cooking with a single pot over a tiny propane tank, it felt really good to be able to stretch out and properly cook, and for a sizeable crowd (c. 15 each night).

I left the Lodge on the morning of Day 83 with my mother, with whom I wanted to share a piece of my experience. We made it past Gold Lake and Long Lake before cutting over towards the Lakes Basin trailhead, where we were intercepted by Katya and our friend Anya. After having lunch amongst the four of us, I then returned to the PCT to continue my northbound journey. This was definitely one of the hardest afternoons I’ve had mentally – to have been in a place that’s like a second home to me and then leave to return to the grind of hiking all day was a challenge made more difficult by the familiarity of the terrain I was still in. Fortunately, this wistfulness subsided a couple of days later, as the reminders of Salmon Lake lessened.

Salmon Lake to Lassen

The trail continues northwest out of the Lakes Basin region along a series of ridges and down into the canyons of the Middle and North Forks of the Feather River.

Not too much to say about the hiking for these few days: lots of forests which are interesting in their own right, but can get a bit monotonous, especially when compared to the high peaks I had left in the High Sierra.

The hiking was mostly relatively easy, with the exception of two huge 4,000 ft+ descents into the forks of the Feather River and corresponding ascents out of them. The Middle Fork is a federally-designated “Wild and Scenic” river and is therefore free of most human interventions, and it is indeed very lovely. The North Fork, by contrast, is basically one big hydroelectric project, with several reservoirs between Lakes Almanor and Oroville. This hydro project was also where the Camp Fire which ravaged the town of Paradise originated (though downstream of where I hiked). I met my father for lunch in Belden, on the North Fork, and hiked up the canyon with him for an hour or two, discussing the electricity infrastructure and forests of the region.

A couple of days later, I descended off of the final Sierran ridgelines and into the lowlands around Mt Lassen.

And I also crossed the midpoint of the PCT, which was a pretty nice milestone.

Lassen Volcanic NP to Burney

At the end of Day 88, my mother, Katya, and Anya joined me for the night, with Katya and Anya hiking with me for the next two days (and my mother driving back home the next morning after the camping experience). We camped about five miles south of where the trail crosses into Lassen Volcanic National Park, apparently the least visited national park in the country. The trail spans 19 miles of parkland, and plastic bear cannisters are required to camp in the park. Having sent mine home after the High Sierra, and with neither Katya or Anya having one, that meant having to do 24 miles in order to avoid camping in the park. By now I’m pretty comfortable with that distance, but it was an impressive and gritty effort by Katya and Anya to do so right out of the gate. We hiked a further 14 miles together the next day before arriving at their car (and I continued another six miles alone in the evening).

The Lassen area, both in the national park and north of it, was a real highlight.

First, since leaving Donner Pass, the Sierras have gradually mellowed and died out as I moved north. While far from the largest, at c. 10,500 feet, Mt Lassen is the southernmost volcano of the Cascade range, where I will be for the remainder of the hike, and whose super-prominent volcanoes will dominate the landscape (as I write this, I’m already in the shadow of Mt Shasta, which, at 14,200 ft, is the second highest Cascade volcano, after Mt Rainier). It’s a nice psychological boost to move into a new range, and to be able to measure progress visually by which volcanoes are visible at any point.

Second, the volcanic landscape is awesome, if a bit painful on the feet. Lassen is an active volcano, and erupted in devastating fashion in 1915. As a result, there are all sorts of active geysers and sulfuric expulsions, as well as lava tubes and hardened lava floes from older volcanic activity. Recent fire activity has also opened up the views, while making the hiking pretty toasty at times.

After Katya and Anya left, I pushed 25 miles through the moonscape to the town of Burney, where the local Assembly of God church has opened up their multipurpose room to hikers for free. I can’t say I agree philosophically with Assembly of God or other similar Evangelical Christian sects, but they’re very kind and generous here without trying to evangelize, and I really appreciate their hospitality. Now time to run a few errands around Burney and hit the trail towards Mt Shasta!

Days 72-78: Southbound Part III

Day 72: Mammoth Lakes (907) to Crater Creek (904)

Day 73: 904 to Vermilion Valley Resort Trail Junction (878)

Day 74: 878 to near Muir Trail Ranch (858)

Day 75: 858 to Muir Pass/Muir Shelter (839)

Day 76: 839 to Upper Palisade Lake (819)

Day 77: 819 to confluence of Woods Creek and South Fork Kings River (800 + 4 mile side trail)

Day 78: 800 + 4 to Road’s End, and drive to Davis (1153)

Highlights: Big time scenery; finishing the southbound section without incident, Muir Shelter, awesome human interactions.

Lowlights: Except at highest elevations, mosquitos make it hard to stop and take it all in; Forgetting my phone at camp and adding five miles to get it.

Mammoth and back out to the trail

Day 72 was very much a “nearo” day, with the main hiking objective being merely to get back on the trail so that I could get in full miles the next day.I didn’t take too many pictures of Mammoth, but it kind of reminds me of Truckee but a bit bigger. Lots and lots of restaurants spread out across town, a very bourgeois central “village” where every building seemed to be a gear shop or a traditional Tirolian restaurant, a lot of ski cabins, and a free trolley that circulates town (really it’s a bus, but with the façade similar to a San Francisco cable car).

Unlike in previous towns, I hardly saw any other PCT hikers, either because I’m now south of the bubble, and/or because the town has more options to offer hikers so they didn’t all descend on a single place. I thought the Mammoth Brewing Company would be a safe bet to find the hikers: great food and beer (their 395 IPA is amazing); no other hikers.

One thing really ground my gears though, which was this vaguely European bakery whose name they styled below, evidently to bring out the Austrian vibes. Apparently nobody told them that German doesn’t have a double K, nor is it ever acceptable (in any language, as far as I know) to put an umlaut on a Y.

Anyway, cute place, but very much a posh ski resort town.

Around 6 pm I got the bus back out to the trail. I was the only passenger on the bus, and wound up chatting the entire time with doubtlessly the most interesting bus driver I’ve ever met (keep in mind that I used to be a bus driver in college, and many of my coworkers/friends were pretty interesting folks). I could probably write an entire post on this dude.

Early in the 30 minute drive, Tom, a trim middle-aged man with an unidentifiable European accent, asked me where I was headed, so I explained that I was hiking on the PCT, assuming he was just some local guy who was familiar with the concept due to proximity but otherwise not an outdoor type (his accent didn’t strike me as odd in a ski town).